Much of our current knowledge is merely provisional. Specifically in the humanities, we can always encounter new evidence, construct unique theoretical frameworks that support novel interpretations, or make use of the progress in other scientific disciplines.1 And such fresh insights in the humanities can subsequently help us to find even more new evidence, to construct further unique theoretical frameworks, and to aid other scientific disciplines in turn.2 These developments do not always entail that scholars had been wrong before, though – quite the contrary! Our understanding may also be merely expanded or enriched. And this can happen for the most pedestrian of reasons. Even one word can suffice! So today we will discuss how one newly discovered word of the Epic of Gilgamesh ushered in a better understanding of this famous tale from ancient West-Asia.

This blog is also available in Dutch.

The Many Faces of Gilgamesh

There is – and probably always was – a multitude of versions of Gilgamesh’ adventures. These stories about the legendary 3d millennium BCE king of the Mesopotamian city state of Uruk, if they at least did come down to us in a form of writing, are today only available in a fragmentary state. The very reason they survived was that they were written on the rather durable medium of clay tablets.3 But these fracture easily, and it is up to modern scholars to puzzle them together and to ascertain what tablet belongs to which known version – or that we found an entirely new tale!

As a result, even the most famous and probably complete version of Gilgamesh’ exploits – the so-called Standard-Babylonian Epic in the Akkadian language – is missing crucial passages. And this fabulous story is often already difficult enough to interpret as it is!4 Consequently, any newly discovered source can upend our erstwhile interpretations. There is, for example, a tablet from Sultantepe (ancient Ḫuzirina) in Türkiye wherein we learn that Gilgamesh’ steadfast companion Enkidu was raised with a gazelle (ṣabītu) for a mother and a donkey (akannu) for a father.5 And as mentioned above, sometimes one novel word can open entire vistas that were hitherto hidden to us.

The Conscience of Uta-Napishtim

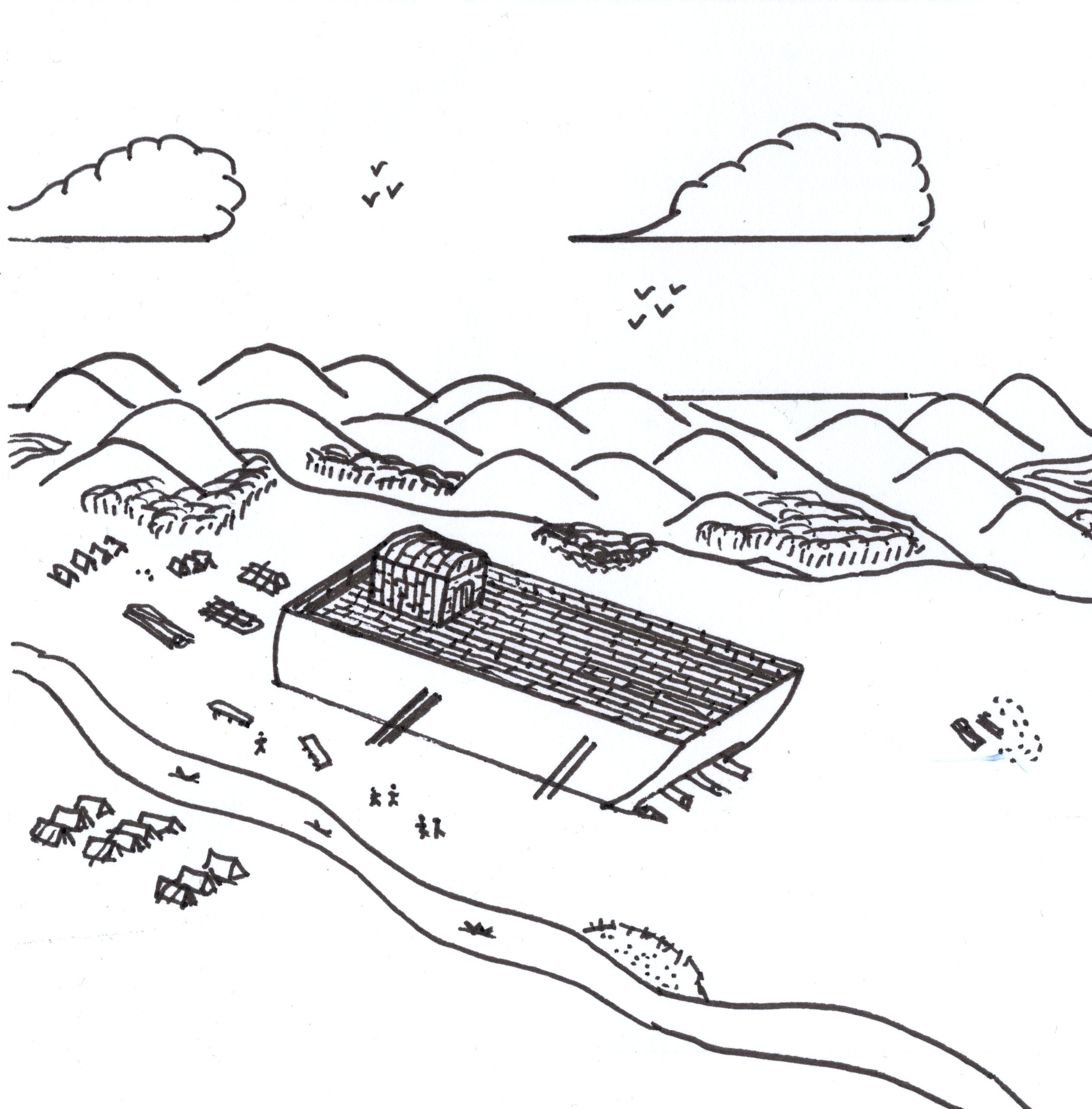

At the end of the Standard-Babylonian Epic, Gilgamesh reaches Uta-Napishtim in his search for immortality.6 This was the man who, along with his household, saved specimen of all living beings from a devastating flood brought down by the god Enlil.7 He is, putting it extremely simply, the Mesopotamian version of the biblical flood hero Noah – of ark fame.8 And here he does indeed tell the story of that flood, to communicate to the visiting heroic king that the circumstances which granted him his immortality can not be recreated for Gilgamesh himself. It is this story, specifically the part where Uta-Napishtim had his ark built, that has relatively recently been made more complete.

In the older translation of the Standard-Babylonian Epic of Gilgamesh in my bookcase, Uta-Napishtim tells his guest about how he provided his work force with a great feast and that he gave wine to them like water from the a river. Though the verb ‘to give’ was not actually read because of damage to the relevant clay tablets.9 While filling in this lacuna, scholars had theorized that ‘to give’ was the word most likely used. But this turned out not to be the case – at least, not for all versions.

Luckily, on a tablet that has only a short time ago been identified as a missing part of the Standard-Babylonian Epic of Gilgamesh through the use of a new computer program, we can read that very word! It turns out that, at least in this version, Uta-Napishtim “lavished” – literally “I lavished”, “aṭḫud[a]” in akkadian – wine on those who had worked on the ark with him.10 The verb ‘to lavish’ is a word which has different connotations than simply giving something to someone. It implies that generous or extravagant amounts were bestowed.11 And according to Benjamin Foster this verbiage indicates even more clearly the troubled conscious of the flood hero.12 Because Uta-Napishtim had lied and told everyone that his ark was built for a purpose that would bring abundance to his community.13 And he knew these people were going to drown while he, his loved ones, and many – many! – animals would be safe on the ark. To help his with his guilt, he therefore spoiled these doomed souls thoroughly.

Conclusion: Progress in the Humanities

There is always something to discover in the humanities. And this is aptly shown by the scholarly saga that we discussed above. Our new, incrementally progressed understanding of at least one version of the Gilgamesh Epic involved a newly identified fragment of that ancient story, as well as a novel scientific instrument that was needed to recognize it as such. And this led us to an insight that we could have hypothesized about, but would have never been able to definitively verify otherwise.

This small but undeniable progress and everything that is needed to facilitate such breakthroughs, is one of the things that makes the humanities so endearingly fascinating, I think. Moreover, we are shown once again how indispensable this discipline is. Not only in furthering other fields and the application of the knowledge created therein, but also in enriching our understanding of the human condition as it was perceived through space and time. And such an enriched understanding may eventually lead to the betterment of that very human condition itself.14

References

- Rens Bod, De Vergeten Wetenschappen: Een Geschiedenis van de Humaniora (Amsterdam: Prometheus, 2020), p. 430-444; Alexander Rosenberg, Philosophy of Social Science (London: Routledge, 2018), p. 6-7, 11-14.

- For a general overview, but with a critical slant, see: Dario Martinelli, Arts and Humanities in Progress: A Manifesto of Numanities (Cham: Springer, 2016). This is, if I may offer one example, also the case with the environmental humanities, see: Sally L. Kitch, “How Can Humanities Interventions Promote Progress in the Environmental Sciences?”, Humanities 2017, 6 (4), p. 76-91.

- Andrew George, The Epic of Gilgamesh: The Babylonian Epic Poem and Other Texts in Akkadian and Sumerian (London: Penguin Books, 2003), p. xiv-xvi. Today, Uruk would have been situated in the south of Iraq, see: Marc van de Mieroop, A History of the Ancient Near East: Ca. 3000 – 323 BC (Malden: Blackwell, 2024), p. 7.

- Martin Worthington, Principles of Akkadian Textual Criticism (Berlin: De Gruyter, 2012), p. 305-307.

- Andrew George, The Babylonian Gilgamesh Epic: Introduction, Critical Edition and Cuneiform Texts (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2003), p. 369-373.

- Alan Lenzi, An Introduction to Akkadian Literature: Contexts and Content (Winona Lake: Eisenbrauns, 2019), p. 119-123.

- Gwendolyn Leick, A Dictionary of Ancient Near Eastern Mythology (London New York: Routledge, 1998), p. 65.

- Peter W. Coxon, “Noah”, in: Karel van der Toorn et al (eds.), Dictionary of Deities and Demons in the Bible (Leiden: Brill, 1999), p. 632.

- George, The Epic of Gilgamesh, p. 88.

- Enrique Jiménez , “New Fragments of Gilgameš Chiefly from the ‘Babylon Collection’”, Kaskal 2020, 17 (1), p. 236-246.

- Angus Stevenson (ed.), Oxford Dictionary of English (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2010), p. 1000. For the precize meaning of the Akkadian verb, see: Martha T. Roth et al (eds.), The Assyrian Dictionary of the Oriental Institute of the University of Chicago: Volume 19 (Ṭ) (Chicago: The Oriental institute, 2006), p. 42.

- Erik Ofgang, “Piecing Together an Ancient Epic Was Slow Work, Until A.I. Got Involved”, The New York Times August 12th 2024, Books.

- George, The Epic of Gilgamesh, p. 89-90.

- Martha C. Nussbaum, Not for Profit: Why Democracy Needs the Humanities (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2016), p. 6-11; Rosenberg, Philosophy of Social Science, p. 27.