If there is one occurrence that many people remember from antiquity, it is that three hundred soldiers from the ancient Greek city-state of Sparta once stood against the much larger army of the Persian king Xerxes.1 This is partly the result of its many depictions in pop culture, including the well-known fantastical – and fairly problematic – retelling in the movie 300 from 2006.2 The second Greco-Persian war, which occurred in the beginning of the fifth century BCE and that saw the aforementioned heroics of the Spartans, was a time of military savvy, masterful intrigue, and uncountable tears. But today I want to focus on one specific aspect, a single word even. I am concerned here with a term that the ancient historian Herodotus uses to describe the thought process of the Spartan king Leonidas I when the latter send most of the other Greeks soldiers away – yes, there were other Greeks present! – and prepared his Spartans for their last stand. That word is τάξις (taxis).3 And Herodotus’ metaphorical use of what ultimately was just a mere technical term, can inform us about the martial ideologies of Greece in that time.

This blog was not only inspired by the one word we will discuss today, but also by the book that brought it to my attention and on which the following is largely based. This is a volume that I got gifted last Halloween and which I finally got around to read before it is the end of October once again: Soldiers & Ghosts: A History of Battle in Classical Antiquity by Jonathan Lendon.4 In this thoroughly sourced and eminently readable work, Lendon teaches us about the role of ideology in ancient Greek and Roman warfare. And this includes metaphors like the one used by Herodotus, which I will discuss today with all those who fear ancient soldiers nor their ghosts!

This blog is also available in Dutch.

Metaphors, Historians, and Hoplites

Metaphors structure both our language and our thinking – as far as we can even separate the two, that is.5 In their enduring volume on the subject, George Lakoff and Mark Johnson describe how the metaphorical concepts we employ, often almost unthinkingly, shape our mindscapes and behaviors.6 And this holds true even when it comes to very mundane things. As such, metaphors influence how we see the world, interact with others, perceive ourselves, et cetera. For example, when English speakers describe time in various broadly accepted ways as a valuable commodity, they are more likely to perceive time as such and act like this is actually the case.7 And this means that in a culture with differently constructed concepts and another language, time may both be viewed and treated differently.8 What’s more, attempts to connect some aspects of our universally shared humanity to certain metaphors that would therefore be inevitable regardless of culture or language – like that warmth, which any human needs, would always be associated with affection – have proven controversial.9 As a result, it is for now still safe to state that studying metaphors can teach us a lot about cultures.

Which brings us to the metaphor that interests us today and which, hopefully, can tell us something about the culture or cultures that Herodotus imagined the Spartan king belonged to.10 Our historian friend is naturally far from the only source on Thermopylae, the mountain pass where the ancient Greeks and ditto Persians clashed. He himself cites other authorities on the battle and tries to find common ground in their accounts.11 And when conveying the thoughts of the Spartan king that interest us, he notes that this is what others have said. And what did they say regarding τάξις, you might ask? From Herodotus’ write-up we learn that when Leonidas send away his Greek allies – save for some who, some willingly and others forced, kept their rear – he announced that the Spartans would not leave their “post”.12 That translation of τάξις does get across what the Spartans subsequently did, but it obscures the metaphorical layer in his specific word of choice.

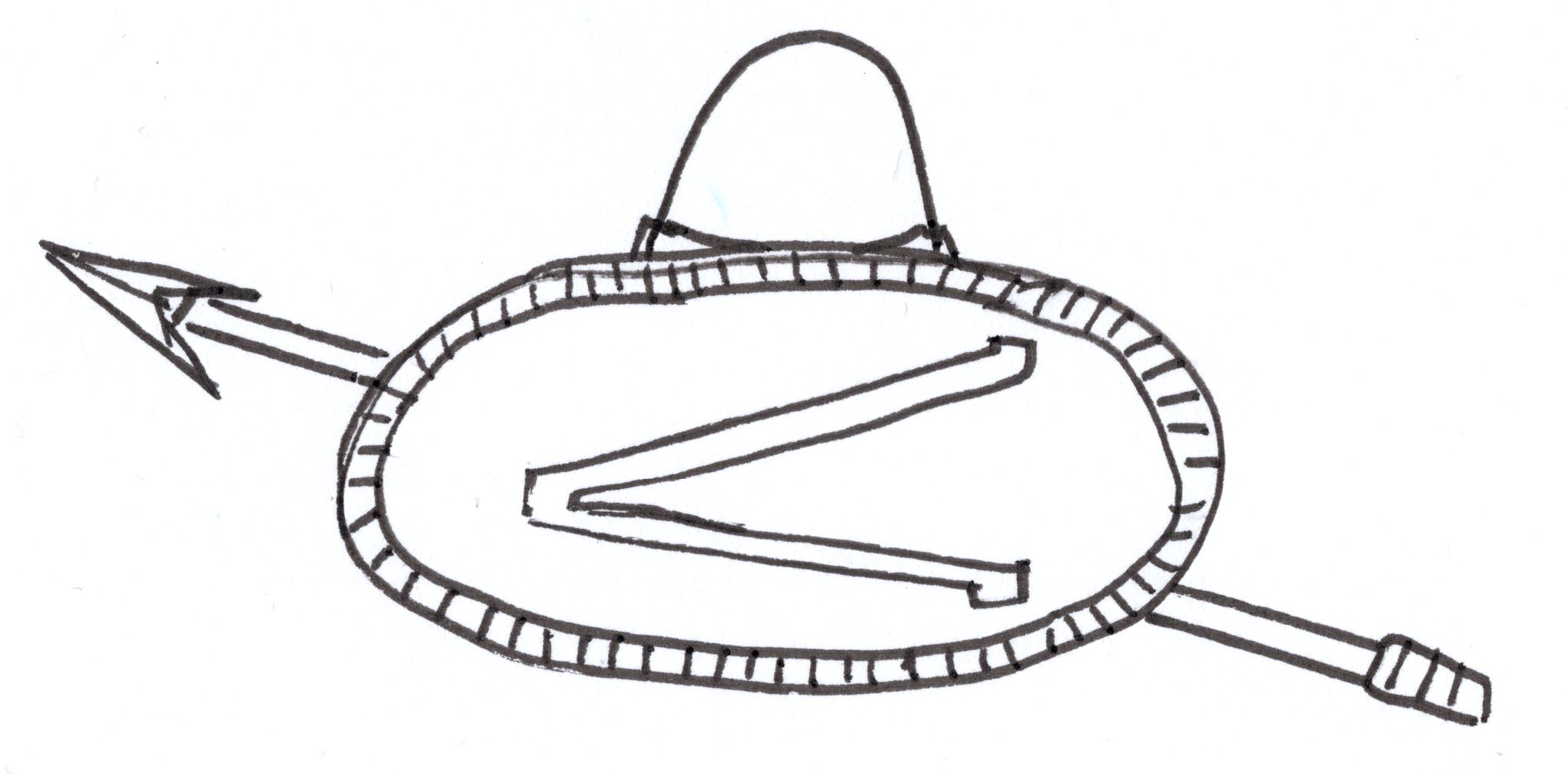

Because τάξις was a term that could also be used in a very confined sense by an ancient Greek: the position a hoplite occupied in the phalanx.13 Some of those last words were probably not familiar to all readers, so allow me explain. A hoplite was a soldier who primarily fought with a shield and a spear, but often had a sword or dagger as backup. We begin to encounter men in this attire on images from the Greek world of the first half of the first millennium BCE. And the Spartan poet Tertaeus describes them in the seventh century of that millennium as heavily armed men who fought rather autonomous on the battlefield, though they could also cooperate.14 But by the fifth century, when our picture becomes clearer, we find them mostly arranged in the so-called phalanx-formation. This meant that they formed tightly packed lines of men, wherein the shield of one soldier would protect the person next to them and they could trust their spears towards the enemy from relative safety. And this formation had a great hold on the ancient Greek imagination.15

Because for a while, clashing phalanxes became the preferred form of warfare in the south of ancient Greece, largely crowding out other ways of fighting like with bow and arrow or on a horse. It is therefore not all that surprising that the courage of a hoplite that held his position in the line became proverbial. And it is equally unremarkable that Herodotus – or those who told him about the battle at Thermopylae – considered it a fitting metaphor to describe the bravery of the Spartans and their king. Our historian wrote his history a few decades after the second Greco-Persian war and lived through the heyday of the hoplite. And we encounter the power of this metaphor also elsewhere. Including in a story, which may have had a basis in reality, wherein a Spartan soldier survived a battle by playing dead but tried to emphasize his courage through arranging his dead comrades in a line approaching a phalanx and retaking his old place therein.16 This strong hold of the hoplite over peoples’ imagination makes you wonder how this very specific kind of warfare became so influential, whether it had to contend with rival ideals, and for how long it lasted.

The Beleaguered Hoplite Ideal

The ideal of soldiers armed as hoplites fighting in a phalanx-formation may have been proverbial, it took a long while to get there and it was never all-encompassing. Lendon postulates that the initial popularity of the hoplite way of war was engendered by the desire to have a clean competition on the battlefield. Soldiers could prove themselves through holding the line alongside their comrades, mostly without arrows or horses interfering at inopportune moments. In a way the phalanxes also represented the city-states that employed the soldiers and their clash could be perceived as the fairest contest that was possible between these polities.17 But many of you may now shrewdly wonder whether it isn’t easy to win the day by trickery if you are pretty sure how your enemy will fight?

Indeed, at no point in time was the hoplite phalanx entirely insulated from tactical surprises. Despite the ideal circumstances I described above, they regularly did have to deal with ambushes, lightly armed spear throwers who never engaged a phalanx within reach of their own weapons, and any other conceivable trick on the papyrus roll.18 And like the famed place of a hoplites in the phalanx, the wiles of cunning generals who employed such tricks also became something that was highly admired in the south of ancient Greece. As such, we see two ideals being influential and practiced alongside each other: the passive courage of holding the line as a hoplite and the use of active deception by commanders to achieve victory with less risk to the lives of their men.

And even the Spartans, whose most reputed martial act was famously compared to exactly that passive courage, valued both of these ideals. They honored Leonidas and his steadfast courage in holding the proverbial line, but they also presented kings who won less bloody victories through trickery with a sacrificial bull.19 Young men at Sparta where both trained in the art of war and the art of deception. Indeed, Sparta was exceptionally prolific in the use of secret codes.20 But before you feel any admiration for this aspect of Spartan society, do not forget that their polity was a terrible dictatorship, perhaps even by ancient Greek standards, built on the gruesome oppression of large groups of people.21 More than a few of those men with Leonidas, about whom we still make movies today, had probably partaken in these abhorrent practices and may have even murdered at least one innocent person.22 As such, the ideal of the hoplite was only that – an ideal that did never fit all warfare in ancient Greece and which could not meaningfully reveal a man’s character.

The foregoing is of course a mere overview of the position of the hoplite and the phalanx in ancient Greek imagination and warfare. There were important differences between localities and throughout time. The city-state of Thebes, for example, reportedly employed a hoplite unit comprised of lovers in order to have them fight valiant for each other. And in the north of the Greek peninsula, the role of cavalry had remained more pronounced. By the way, one of the reasons the Spartans were initially so successful, was because they were earlier adopters of the belief that you can teach both marital prowess and courage through training and that they recruited soldiers that did not have a high societal standing per se.23 Perhaps the most remarkable thing about the hoplite ideal is therefore the fact that it survived for so long. Even when other military tactics proved fruitful, both in general and against phalanxes in particular, many ancient Greeks still admired and continued to try and practice the hoplite ideal. Its relative prestige would only begin to weaken when Alexander III of Macedon – sometimes called ‘the great’, by those who think they can fix him – and his father upended the entire balance of power in the region towards the end of the fourth century BCE.24

Conclusion: Three Hundred Hot Takes

We encountered a lot of stories in the foregoing about both bravery and smarts winning battles. But many of these tales, perhaps even some of those about Leonidas and his three hundred colleagues, may have been just that – fictional narratives.25 Though even if some of the most outlandish stories did not actually happen, they still inspired actual outlandish behavior – brave as well as ill-advised – about which our surviving evidence is much more conclusive. As such, the hoplite ideal and the adjacent metaphors remain important if we want to reconstruct as well as understand the south of Greece in antiquity and especially during the fifth and fourth centuries before our common era.26

And understanding king Leonidas’ motives and thoughts, which Herodotus conveyed to us with the elegant metaphor of τάξις, is perhaps more important than other matters. Because ancient Greece in is often abused for unsavory political ends in our contemporary world – and specifically the Spartans, including their last stand at Thermopylae. Even though Sparta, however terrible it was, does not entirely fit the modern totalitarian ideals that are often associated with it.27 And this is again evidenced by our linguistic detour today. The way in which the people of ancient Greece in general and Spartan citizens in particular saw the world, including their metaphors, very much differed from modern sensibilities. Such observations will of course not prevent the abuse of the ancient world, but a thorough understanding of the deep past does show the mind-blowing variety of the human condition and that antiquity cannot simply be appropriated to promote one worldview – let alone an exclusionary one.28

To end on a less grim note: we also saw today that a simple word from the deep past can be positively fascinating. To wit, we did have to use a lot of our own vocabulary to explain the layers of meaning and background of such a short and unassuming word as τάξις. And there is so much we can still learn – discoveries that are still to be made. Even about dead languages which we are able to read for a very long time now, including ancient Greek. Last weekend, I lost myself in the interesting scholarship on the loanwords in that language from Luwian, another tongue from antiquity which was mostly spoken in Anatolia.29 And did you know that the phonetics of ancient Greek can in part be reconstructed using my beloved Gothic?30 Words and metaphors can teach us much about the lost societies of yesteryear and hopefully we can revisit those efforts soon!

References

- Paul Cartledge, Thermopylae: The Battle that Changed the World (London: MacmillanAnton, 2006); Anton Powell, “Sparta: Reconstructing History from Secrecy, Lies and Myth”, in: Anton Powell (ed.), A Companion to Sparta – Volume I (Chichester: John Wiley & Sons, 2017), p. 14.

- Emma Stafford, “The Curse of 300? Popular Culture and Teaching the Spartans”, Journal of Classics Teaching 2016, 17 (33), p. 12; Mike Waldner-Scott, “The Spartan Legacy in the Contemporary Popular Culture; A Case Study of The 300”, Sparta: Journal of Ancient Spartian & Greek History, 2009, 5 (1), p, 17.

- Alfred D. Godley, Herodotus’ The Persian Wars – Book 5-7 (London: Harvard University Press, 1926), p. 536; Robert Strassler (ed.), The Landmark Herodotus: The Histories (New York: Anchor Books, 2007), p. 591.

- Jonathan E. Lendon, Soldiers & Ghosts: A History of Battle in Classical Antiquity (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2005).

- Leonid Perlovsky, “Language and Cognition”, Neural Networks 2009, 22 (3), p. 247-248.

- George Lakoff & Mark Johnson, Metaphors We Live by (Chicago: Chicago University Press, 2003), p. 2.

- Ibidem, p. 8.

- Ibidem, p. 4-5.

- George Lakoff, “Language and Emotion”, Emotion Review 2016, 8 (3), 270; Cliff Goddard, Comment: Lakoff on Metaphor – More Heat Than Light, Emotion Review 2016, 8 (3), p. 277.

- Lendon, Soldiers & Ghosts, p. 61.

- Pietro Vannicelli, “To Each His Own: Simonides and Herodotus on Thermopylae”, in: John Marincola (ed.), A Companion to Greek and Roman Historiography (Chichester: Wiley-Blackwell, 2007), p. 315.

- Strassler, The Landmark Herodotus, p. 591.

- Lendon, Soldiers & Ghosts, p. 61; Fred Muller & Johannes H. Thiel, Beknopt Grieks-Nederlands Woordenboek, Edited by Wim den Boer (Groningen: Wolters-Noordhoff, 1969), p. 714. And Herodotus knew this, as he uses the term in this meaning elsewhere, see for example: Hans van Wees, “Thermopylae: Herodotus versus the Legend”, in: Lidewij van Gils, Irene de Jong & Caroline Kroon (eds.), Textual Strategies in Ancient War Narrative: Thermopylae, Cannae and Beyond (Leiden: Brill, 2019), p. 33.

- Lendon, Soldiers & Ghosts, p. 43.

- Henk Singor, Grieken in Oorlog: Veldtochten en Veldslagen in het Klassieke Griekenland (Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press, 2006), p. 80-82, 86-88. It is argued that the hoplite phenomenon can also be connected to political developments, see: Frits Naerebout & Henk Singor, De Oudheid: Grieken en Romeinen in de Context van de Wereldgeschiedenis (Amsterdam: Ambo, 2010), p. 110-112.

- Lendon, Soldiers & Ghosts, p. 40-41. I have to remain a little bit vague here, as the specifics of the phalanx-formation are still debated. For a variety of overviews and syntheses of the various scholarly positions, see: Roel Konijnendijk, Classical Greek Tactics (Leiden: Brill, 2018); Roel Konijnendijk, Cezary Kucewicz & Matthew Lloyd (eds.), Brill’s Companion to Greek Land Warfare Beyond the Phalanx (Leiden: Brill, 2021); Everett Wheeler & Barry Strauss, “Battle”, in: Philip A.G. Sabin, Hans van Wees & Michael Whitby (eds.), The Cambridge History of Greek and Roman Warfare (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2007), 399-433.

- Lendon, Soldiers & Ghosts, p. 51-56; 62-63.

- Ibidem, p. 92-106; Singor, Grieken in Oorlog, p. 88-89.

- Lendon, Soldiers & Ghosts, p. 85–87.

- Powell, “Sparta: Reconstructing History from Secrecy, Lies and Myth”, p. 25.

- Thomas Figueira, “Helotage and the Spartan Economy”, in: Anton Powell (ed.), A Companion to Sparta – Volume II (Chichester: John Wiley & Sons, 2017), p. 589; Powell, “Sparta: Reconstructing History from Secrecy, Lies and Myth”, p. 26; Hans van Wees, “Luxury, Austerity and Equality in Sparta”, in: Anton Powell (ed.), A Companion to Sparta – Volume I (Chichester: John Wiley & Sons, 2017), p. 227. The scholarly debate over the degree of difference between Sparta and the other city-states of ancient Greece still continues, see: Stephen Hodkinson, “Sparta: An Exceptional Domination of State over Society?”, in: Anton Powell (ed.), A Companion to Sparta – Volume I (Chichester: John Wiley & Sons, 2017), p. 51; Paul Cartledge, “Foreword”, in: Anton Powell (ed.), A Companion to Sparta – Volume I (Chichester: John Wiley & Sons, 2017), p. xv-xvi. For a brief overview of Sparta’s history, see: Naerebout & Singor, De Oudheid, p. 112.

- Stefan Lin, “Zur Entstehungsgeschichte der Spartanischen Krypteia”, Klio 2006, 88 (1) , p. 34-35; Thomas Figueira, “Helotage and the Spartan Economy”, p. 567.

- Lendon, Soldiers & Ghosts, p. 110; Singor, Grieken in Oorlog, p. 85; Naerebout & Singor, De Oudheid, p. 112.

- Lendon, Soldiers & Ghosts, p. 106, 114.

- Powell, “Sparta: Reconstructing History from Secrecy, Lies and Myth”, p. 14, 23-24; Michael A. Flower, “Simonides, Ephorus, and Herodotus on the Battle of Thermopylae”, Classical Quarterly 1998, 48 (2), p. 366.

- Powell, “Sparta: Reconstructing History from Secrecy, Lies and Myth”, p. 15.

- Hodkinson, “Sparta”, p. 44-45.

- Louie D. Valencia-García, “Far-Right Revisionism and the End of History”, in: Louie D. Valencia-García (ed.), Far-Right Revisionism and the End of History: Alt/Histories (Abbingdon: Routledge, 2020), p. 3. Curtis Dozier, “Hate Groups and Greco-Roman Antiquity Online: To Rehabilitate or Reconsider?”, in: Louie D. Valencia-García (ed.), Far-Right Revisionism and the End of History: Alt/Histories (Abbingdon: Routledge, 2020), p. 258-263,

- Craig Melchert, “Luwian”, in: Rebecca Hasselbach-Andee (ed.), A Companion to Ancient Near Eastern Languages (Hoboken: John Wiley & Sons, 2020), p. 247. On this specific cross cross-fertilization in the eastern Mediterranean, see: Ilya Yakubovich, “Phoenician and Luwian in Early Iron Age Cilicia”, Anatolian Studies 2015, 65 (1), p. 36-41.

- Ville Leppänen, “Gothic Evidence for Greek Historical Phonology”, in: Felicia Logozzo & Paolo Poccetti (eds.), Ancient Greek Linguistics: New Approaches, Insights, Perspectives (Berlin: De Gruyter, 2017), p. 36. For more about Gothic, visit my previous blog on this fascinating ancient language!