You know what is a sobering fact which keeps me with both my feet firmly on the ground? That there was once a time – unbelievable but true – in which people did not venerate the great and ancient Mesopotamian god Marduk. And you know what’s even more indicative of the mere relative importance of everything? The fact that at one point people stopped venerating Marduk! Today we are going to look at the rise and fall of this imposing Mesopotamian god, of whom no-one in the second millennium BCE would have believed that their prominence could ever diminish.1 But nothing lasts forever and, as one age follows another, even the gods may become a mere historical footnote.Welcome to the second part of my always uplifting series on forgotten gods!

As said, the god Marduk was mainly at home in the ancient period and throughout an area that we call Mesopotamia. This historical place is currently situated in the modern state of Iraq, with some parts stretching into Syria and Türkiye. Our written sources from Mesopotamia, as well as many of the adjacent regions, consist mainly of clay tablets.2 Most of these tablets were inscribed with the famous cuneiform script, which rendered several ancient languages. From now obscure tongues, like Eblaite, to the oldest known Indo-European language, Hittite.3 To understand the life and times of Marduk, we mainly need two ancient languages: Sumerian and Akkadian. For clarity and as is customary, I shall render Sumerian word signs in BOLD SMALL CAPITALS, with the accompanying sounds signs merely boldened, and I will italicize Akkadian.4 And this due diligence would perhaps have pleased Marduk himself, as his son Nabû used to be the Mesopotamian god of writing.5

This blog is also available in Dutch.

The Rise of Marduk

It is difficult to ascertain on the bases of our evidence whether the cult of Marduk existed prior to the second millennium BCE.6 But what is certain, is that Marduk’s prominence coincided with the increasing political power of the city of Babylon. Specifically when king Hammurabi, who reigned from 1792 to 1750 BCE, brought much of Mesopotamia under the control of his city, the fortunes of Marduk were advanced with his.7 The god even became a literal star, as the celestial body that we now know as Jupiter was named “Marduk Star”.8 And Marduk’s eminence was not strictly tied to the Old-Babylonian polity that had brought him to the fore. Eventually the mighty Neo-Assyrian Empire, which was based to the north of Babylon and controlled large swathes of West-Asia in the first half of the first millennium BCE, would even adopt the Marduk theology as it was developed in Babylonia.9 And in the Neo-Babylonian Empire that would be established following the collapse of the Neo-Assyrian state, the priests associated with Marduk proved to be a powerful faction.10

And the cult of Marduk that was maintained by that priesthood, was certainly something to behold! Marduk’s main temple was the Esagila complex in Babylon – surprise, surprise – and it included a mighty ziggurat.11 This was an enormous, stepped pyramidal structure which bore the Sumerian name E2.TEMEN.AN.KI or ‘Temple of the Foundation of Heaven and Earth’.12 By the way, if I was offered the chance to go back in time, one of the events I would surely visit, is the so-called Akītu-festival in ancient Babylon. This impressive festival inaugurated the new year and renewed the relationship between the king as a representative of the human population and the divine.13 Perhaps more importantly for us aspiring time travelers who are interested in Marduk, this was also the chance for ordinary people to see the statue of that god, which was though to be indeed an actual manifestation of the divine presence.14 Because this was also the occasion that Marduk’s lordship over the other gods was ritually confirmed.15 And through his giant temple complex and such festivals, Marduk was an economic and cultural factor outside of strictly religious adherence.16

The ascension of Marduk appears to have come at the relative expense of some other gods, though. He often acquired attributes of these gods or supplanted them in their own mythology. For instance, Marduk usurped the position of a god of healing, magic, and the underground waterways named Asalluhi. In this way he gained these divine functions, as well as became the son of the important god that was known in Sumerian as Enki and in Akkadian as Ea.17 The aforementioned rise of Marduk also happened, among other strategies, through myths wherein this Babylonian god alone could defeat the enemies of the gods and restore or bring order to the world.18 In the most famous of these, the creation myth Enuma Elish, Marduk not only became the head of the Mesopotamian pantheon but he also gained fifty titles that were partly taken over from other deities.19 And some of these myths were simply appropriated from other gods, like the example we will now discuss.

The Founding of Eridu/Babylon

As an example of Marduk’s elevated position over the other gods, I wanted to share with you a text that is relatively little known outside academia and which truly fascinates me. Since its modern rediscovery it has been known under many monikers, the most salient of which are Marduk, Creator of the World and The Founding of Eridu.20 Complicating this matter is the fact that the name ‘Eridu’ is probably used in this text as a label for Babylon. This is, among other clues, indicated by the fact that the quintessentially Babylonian temple complex Esagila is said to have been situated there!21 So to stay safe, I follow Kerstin Maiwald and call the text The Founding of Eridu/Babylon.22

In this bilingual incantation, wherein each line is written in both Sumerian and Akkadian, Marduk first creates the world and then inaugurates the order that was known to the Mesopotamians writing, reading, or hearing this story. More relevant to us today, though, is the fact that this text seems to have once featured another god. One that resided in the aforementioned town of Eridu and whom we already met above. A god who, as we saw, was known as Enki to the Sumerians and Ea to the Akkadians.

That this text once featured Enki/Ea as the main creator god can be substantiated, in my opinion, with three arguments. These are: a. the aforementioned equation of Eridu with Babylon; b. a peculiar designation of Marduk in the Sumerian version; and c. outright written evidence that Enki/Ea once was the main character of this story.

To start with Eridu, this was in itself a famous city. In fact, it was long viewed as the first city and that is probably the reason that Babylon was designated with that name in this text. To attain the prestige of the first created settlement. As Eridu was the city where Enki/Ea himself was thought to reside, this is our first clue that the text once pertained to this god instead of Marduk.23

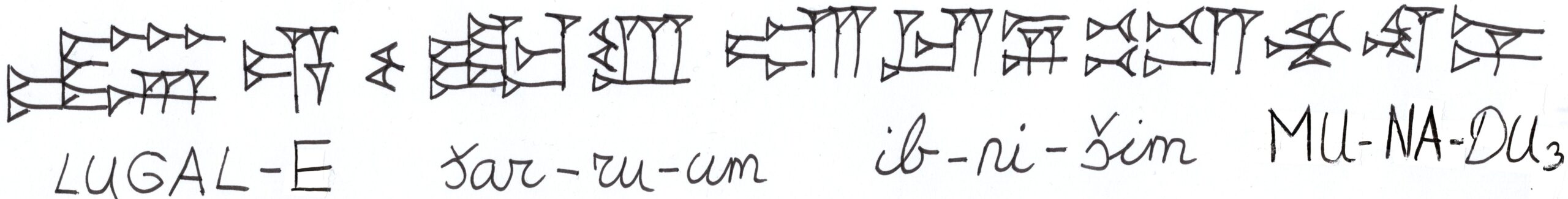

Furthermore, in the line that describes how Marduk first creates dry land, his name is spelled as Gilimma in the Sumerian variant. Let us take a look at that portion the text for a moment:24

l. 17 DGI–LIM–MA GIDIRI I–BI2-na a nam-mi-ni-in-KEŠDA

Dmarūtuk a-ma-am ina pa-an me-e ir-ku-us

l. 18 SAḪAR-ra i3–MU2-a KI A–DAG nam-mi-in-DUB

e-pi-ri ib-ni-ma it-ti a-mi iš-pu-uk

l. 19 DIĜIR-re-e-ne KI-TUŠ ŠA-DU10-ga bi-in-du2-ru-ne-eš-a-ba25

IlāniMEŠ ina šu-bat ṭu-ub lib-bi ana šu-šu-bi

l. 17 Marduk knotted a raft on the surface of the waters,

l. 18 He made earth and heaped it up on the raft

l. 19 That the gods should be settled in a dwelling of their pleasure

Gilimma, as you have probably guessed, was another name or title for Enki/Ea. And this is one of the names that Marduk was explicitly awarded in the aforementioned creation myth Enuma Elish.26 Another clue, perhaps, that points to a former role of Enki/Ea in older versions of this text.

But our third piece of evidence is the most convincing, I think. We have an actual fragment of a version of this text – if our scholarly reconstruction is right – that does mention Enki/Ea by these very names! If we want to substantiate that last claim, though, we first have to get acquainted with the curious layout of this text. As said, the text is bilingual. More specifically, like we saw with the fragment above, we have a Sumerian and an Akkadian version. But these do not alternate, like in my presentation. On the actual clay tablet in which the text was inscribed, each line opens with the first half of the Sumerian sentence, then follows the entire Akkadian sentence, before the final half of the Sumerian sentence closes out the line.27 And this arrangement was not uncommon for texts like these from southern Mesopotamia in the 1st millennium BCE.28 I can imagine that it is hard to visualize, though. So let me give you a fictional sample of this structure, made up entirely by little old me, to make this arrangement less abstract. For clarity’s sake I have written the Sumerian translation for once solely with capitals, and the sentence means: The king built it for her.

Why is this relevant for our evidence? Well, in our best preserved manuscript of this text – the one we already read above and which incessantly mentions Marduk – the first part of line 32 is missing. And due to the arrangement of the text, we have only the last part of both the Akkadian and Sumerian sentences left:29

l. 32 […] ĜIŠGI PA-RIM4 bi-[in-GAR]

[…] tam-tim a-pa na-ba-la iš-ku-un

l. 32 […] turned the reed-beds into dry land.

We did find a fragment of a different clay tablet that fits exactly with that damaged part of the text, though. And, lucky for me, the lay-out is also simpler! The Sumerian and Akkadian sentences just alternate. But lo and behold! Here Enki/Ea is mentioned as the one doing the creation deeds:30

l. 3-4 DEN-KI A-AB-BA-ke4 ĜIŠGI PA-RIM4 […]

Dea31 tam-tim a-pu u na-ba-lu […]

l. 3-4 Enk/Ea […] the reed-beds into dry land.

The right side of the clay tablet fragment is broken, so here too both lines end before the completion of the sentences. But because of the curious layout of our better preserved manuscript, we have enough information to be certain that this small fragments indeed fits with both the Sumerian and Akkadian sentences found in line 32 of the version we discussed earlier. And as we have both the Sumerian and the Akkadian, the name of the god is less likely to be a mistake or the consequence of the lack of knowledge of Sumerian that some experts have discerned in this text.32 And at the beginning of both sentences we read clearly a way to write the actual name of Enki/Ea with cuneiform in the respective language. In combination with what we know about the replacement of Eridu by Babylon and the adoption of the title Gilimma, one could convincingly argue that there was not only an earlier version of this text, but that it was also specifically dedicated to Enki/Ea.33

And this brings us to the question lurking under this discussion of Marduk’s ascension. How could such a prominent god – one that usurped the position and stories of other deities – ever be forgotten?

Marduk Fading

The local belief in Marduk is difficult to pin down. But it is worth noting that only relatively late after Marduk had began his ascension, do we see the name of the god as an element in the names of everyday people, on private seals, and in personal prayers.34 And despite its prominence and influence, the cult of Marduk was never entirely secure. On occasion the cult statue was even stole by rival states, for instance, and had it had to be retaken by the Babylonians. But even these events could be used to further the position of Marduk. Some of the stories that elevate him above the other gods, precisely stem from such a homecoming of the cult statue. 35

When Babylon became part of larger empires, from the Assyrians and the Persians, to the heirs of Alexander III of Macedon, Marduk was no longer the (sole) god who conferred earthly power on kings and the fortunes of his cult varied. Some of these new overlords supported the cult and maintained the Esagila complex, while others tried to destroy it and diminish the importance of the cult of Marduk.36 But after the aforementioned relatively slow start, the worship of Marduk had taken root in Mesopotamia in general and Babylon in particular. And in a few of these parts, the old gods and their cults long remained important to people’s social and religious life irregardless of who ruled them – with Marduk prominently included among them.37

The real change would come when Mesopotamia was incorporated in the Parthian Empire in the second century BCE. And at the beginning of our common era cuneiform writing had all but disappeared and slowly but surely the beliefs of the populace became an – exciting! – mixture of the tenets of the various Assyrian, Babylonian, Persian, Arameic religions, as well as Judaism and Christianity – with more options on the horizon.38

Still the erstwhile cult of Marduk was not entirely forgotten. An account from the third century CE tells us how people would visit the ruins of Babylon and gather at the Esagila complex to worship at the remains of its once mighty ziggurat.39 Afterwards, our textual and archaeological sources are mostly silent. And the next time that we indisputably meet Marduk, as far as I could find, it is in a treatise from the sixth century CE by the philosopher Damascus. He cites the genealogy of the Mesopotamian gods as it could be found in the creation myth Enuma Elish – and fairly accurate so! It may be a small comfort, that one of the last mentions of the Mesopotamian gods in late antiquity refers to the epic story which elevated Marduk to the savior of the gods and the head of their pantheon.40

Conclusion: Gods Never Really Die, Do They?

At the height of his popularity, Marduk was simply known in many of our Akkadian texts as bēly, or ‘the lord’.41 It was honestly not necessary to indicate which lord was meant– if not specified, most people would probably just assume it was Marduk. And as we saw, the worship of Marduk survived the city of Babylon itself. While the city was largely abandoned around the first century CE, the Esagila complex remained a focal point of economic and cultural activity for circa two hundred more years.42 But the cult of Marduk was now a private matter. For instance, when the Roman emperor Trajan entered the ruins of Babylon early in the second century CE, he did not sacrifice to Marduk like Alexander III of Macedon had done some four hundred years earlier while he was dismantling the Persian Empire.43 And who knows how long such an underground movement did persist, before finally succumbing to the sands of time?

Though Marduk nor his cult would disappear without leaving at least some traces. In late antiquity, the king of Hatra, now in northern Iraq, named the main temple of his city the Esagila and referred to the sun-god that was worshiped there as ‘Bel’.44 Moreover, the cult of Bel as it had taken shape in the ancient desert city of Palmyra, which lay in the area of what is today Syria, was imported to Rome – yes, that Rome! – at the end of the third century CE.45 And if we fast forward to our current era, we may observe that Marduk is present in a book that remains important to many religious people worldwide: the Bible.46 Ancient Mesopotamia is also still used to claim modern political authority, perhaps most notoriously by the Iraqi dictator Saddam Hussein. And Hussein harkened back to famous ancient benefactors of Marduk, including king Hammurabi of Babylon.47 Lastly, there are all the other cultural appearances that Marduk still regularly makes, from metal bands to hoaxes and conspiracy theories.48 Now that I think about it: gods are, in a sense, very much like artists. Even if they become forgotten, they live on through their cultural legacy – for better and for worse.

References

- Takayoshi Oshima, “The Babylonian God Marduk”, in: Gwendolyn Leick (ed.), The Babylonian World (Abbingdon: Routledge, 2007), p. 348.

- Christopher Woods, “The Emergence of Cuneiform Writing”, in: Rebecca Hasselbach-Andee (ed.), A Companion to Ancient Near Eastern Languages (Hoboken: John Wiley & Sons, 2020), p. 27, 33.

- Amalia Catagnoti, “Eblaite”, in: Rebecca Hasselbach-Andee (ed.), A Companion to Ancient Near Eastern Languages (Hoboken: John Wiley & Sons, 2020), p. 149-151; Theo P.J. van den Hout, The Elements of Hittite (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2011), p. 1-2.

- For Sumerian, see: Abraham H. Jagersma, A Descriptive Grammar of Sumerian (Dissertation Leiden University, 2010), p. 28-29. In Akkadian texts, we often encounter Sumerian word signs instead of their Akkadian equivalents as a sort of shorthand writing. These sings, modern scholars transliterate as CAPITALS. With the exception of determinatives – signs that indicate merely the meaning of words, but are not part of the spoken language – I have replaced these here with their Akkadian equivalents for reader convenience, see: John Huehnergard, A Grammar of Akkadian (Winona Lake: Eisenbrauns, 2005), p. 109. See also my blog on the logo of Bildungblocks.

- The worship of Nabû may have come to Mesopotamia in the early second millennium BCE and before he became Marduk’s son, he was seen as his minister, see: Jeremy A. Black & Anthony Green, Gods, Demons, and Symbols of Ancient Mesopotamia: An Illustrated Dictionary (Austin: University of Texas Press, 1992), p. 133-134.

- One way of writing his name in cuneiform, AMAR.UTU, appears to have been attested in the third millennium BCE, see: Oshima, “The Babylonian God Marduk”, p. 356, note 2. But the inconclusiveness of this evidence supports conclusions both ways, see for example: Black & Green, Gods, Demons, and Symbols of Ancient Mesopotamia, p. 127; Oshima, “The Babylonian God Marduk”, p. 348.

- Ivan Hrůša, Ancient Mesopotamian Religion: A Descriptive Introduction (Münster: Ugarit Verlag, 2015), p. 57.

- Francesca Rochberg, “Mesopotamian Cosmology”, in: Daniel C. Snell (ed.), A Companion to the Ancient Near East (Hoboken: John Wiley & Sons, 2005), p. 327.

- Paul-Alain Beaulieu, “World Hegemony, 900–300 BCE”, in: Daniel C. Snell (ed.), A Companion to the Ancient Near East (Hoboken: John Wiley & Sons, 2005), p. 54.

- Sarah C. Melville, “Royal Women and the Exercise of Power in the Ancient Near East,”, in: Daniel C. Snell (ed.), A Companion to the Ancient Near East (Hoboken: John Wiley & Sons, 2005), p. 227.

- Oshima, “The Babylonian God Marduk”, p. 355.

- Andrew R. George, “The Tower of Babel: Archaeology, History and Cuneiform Texts”, Archiv für Orientforschung 2005, 51 (1), p. 77. For ziggurats in general, see: Black & Green, Gods, Demons, and Symbols of Ancient Mesopotamia, p. 187-189.

- The Akītu-festival is a broad topic, which is best saved for another blog. For a general outline and the fact that there were multiple of these festivals throughout the year, though the New Year Festival was the most prominent, see: Nicole Brisch, “Ancient Mesopotamian Religion”, in: Daniel C. Snell (ed.), A Companion to the Ancient Near East, 2nd Edition (Hoboken: John Wiley & Sons, 2020), p. 330-331.

- For cult statues in general, see: Hrůša, Ancient Mesopotamian Religion, p. 67-73. For Marduk specifically, see: Oshima, “The Babylonian God Marduk”, p. 355-356.

- Hrůša, Ancient Mesopotamian Religion, p. 58.

- Oshima, “The Babylonian God Marduk”, p. 355.

- JoAnn Scurlock, “Ancient Mesopotamian Medicine”, in: Daniel C. Snell (ed.), A Companion to the Ancient Near East (Hoboken: John Wiley & Sons, 2005), p. 313; Oshima, “The Babylonian God Marduk”, p. 349. For those interested, there is an excellent PhD-thesis written on Asalluhi, see: Andreas Johandi, The God Asar-Asalluhi in the Early Mesopotamian Pantheon (Tartu: Dissertation University of Tartu, 2019).

- Tawny L. Holm, “Literature”, in: Daniel C. Snell (ed.), A Companion to the Ancient Near East (Hoboken: John Wiley & Sons, 2005), p. 256.

- Oshima, “The Babylonian God Marduk”, p. 349; Hrůša, Ancient Mesopotamian Religion, p. 57.

- For those interested, this story has been primarily referred to by three different kinds of designations: a. those referencing Eridu’s founding; b. those centering Marduk’s acts of creation; and c. those that emphasize the presumed ritual use of the text. For examples of all three, see: Wilfred G. Lambert, Babylonian Creation Myths (Winona Lake: Eisenbrauns, 2013), p. 366; Benjamin R. Foster, Before the Muses: An Anthology of Akkadian Literature, 3rd Edition (Bethesda: CDL press, 2005), p. 487; Claus Ambos, Mesopotamische Baurituale aus dem 1. Jahrtausend v. Chr. Dresden: Islet, 2004), p. 200.

- Lambert, Babylonian Creation Myths, p. 200, 367.

- Kerstin Maiwald, Mesopotamische Schöpfungstexte in Ritualen: Methodik Und Fallstudien Zur Situativen Verortung (Berlin: De Gruyter, 2021), p. 413.

- Lambert, Babylonian Creation Myths, p. 368-369; Black & Green, Gods, Demons, and Symbols of Ancient Mesopotamia, p. 77.

- Manuscript BM 93014 (82-5-22), obverse, see: Leonard W. King, Cuneiform Texts from Babylonian Tablets, &c. in the British Museum – Part XIII (London: The Trustees of the Brittish Museum, 1901), plate 36. For this the cuneiform and this transliteration, see: Ambos, Mesopotamische Baurituale aus dem 1. Jahrtausend v. Chr., p. 202-203; Lambert, Babylonian Creation Myths, p. 372-273. Mark Cohen disagrees with the translation of lines 17 and 18. He envisions – admittedly tentatively – Marduk working with smoke or incense, see: Mark E. Cohen, An Annotated Sumerian Dictionary (Winona Lake: Eisenbrauns, 2023), p. 1124.

- For those noticing the deviating pattern: the verbal stem is written here phonetically instead of with a word sign. It pertains to the verb DURUM, the plural of ‘to sit’, see: Jagersma, A Descriptive Grammar of Sumerian, p. 111.

- Lambert, Babylonian Creation Myths, p. 368; Ambos, Mesopotamische Baurituale aus dem 1. Jahrtausend v. Chr., p. 203.

- Sometimes, but not always, the first half of the Sumerian sentence is delineated from the Akkadian sentence with a divider consisting of two Winkelhaken (𒑱), see: Rykle Borger, Mesopotamisches Zeichenlexikon (Münster: Ugarit Verlag, 2003), p. 184-185. To retain clarity and as these are not represented in most modern text editions, I have omitted them here.

- For this layout as it can be found on the actual tablet, see: King, Cuneiform Texts from Babylonian Tablets, &c. in the British Museum – Part XIII, plate 35-39. For the history and prevalence of such textual arrangements, see: Jerold S. Cooper, Sumero-Akkadian Bilingualism (Chicago: Dissertation University of Chicago, 1969), p. 106.

- For this transliteration and translation, see: Ambos, Mesopotamische Baurituale aus dem 1. Jahrtausend v. Chr., p. 204; Lambert, Babylonian Creation Myths, p. 373. For the actual damage, see: King, Cuneiform Texts from Babylonian Tablets, &c. in the British Museum – Part XIII, plate 37.

- Manuscript BM 54652 (82-5-22, 972), reverse. See for cuneiform, transliteration, and translation: Ambos, Mesopotamische Baurituale aus dem 1. Jahrtausend v. Chr., p. 204-205, 262.

- Written with the cuneiform sign IDIM that can be read as the name of the god, see: Lambert, Babylonian Creation Myths, p. 372; Ambos, Mesopotamische Baurituale aus dem 1. Jahrtausend v. Chr., p. 204.

- Lambert, Babylonian Creation Myths, p. 368; Foster, Before the Muses, p. 487.

- Lambert, Babylonian Creation Myths, p. 368-369.

- Oshima, “The Babylonian God Marduk”, p. 349.

- Hrůša, Ancient Mesopotamian Religion, p. 58; Oshima, “The Babylonian God Marduk”, p. 351; Foster, Before the Muses, p. 376.

- And not even all Babylonian kings were sympathetic to Marduk, see: Hrůša, Ancient Mesopotamian Religion, p. 58. Note that some stories about neglecting or opposing the cult of Marduk may be embellishments or fabrications for political purposes, see: Stephanie Dalley, “Occasions and Opportunities: Persian, Greek, and Parthian Overlords”, in: Stephanie Dalley (ed.), The Legacy of Mesopotamia (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1998), p. 38.

- Paul-Alain Beaulieu, “Histories – Mesopotamia”, in: Sarah Iles Johnston (ed.), Religions of the Ancient World: A Guide (Cambridge: The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 2004), p. 169, 172; Alison Salvesen, “The Legacy Of Babylon And Nineveh In Aramaic Sources”, in: Stephanie Dalley (ed.), The Legacy of Mesopotamia (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1998), p. 152.

- Lucinda Dirven, “Religious Continuity and Change in Parthian Mesopotamia: A Note on the Survival of Babylonian Traditions”, Journal of Ancient Near Eastern History 2014, 1 (2), p. 201-223; Paul-Alain Beaulieu, “Histories – Mesopotamia”, p. 172.

- Oshima, “The Babylonian God Marduk”, p. 356. For how ruined Babylon was or wasn’t, see note 40 below.

- Paul-Alain Beaulieu, “Histories – Mesopotamia”, p. 172.

- Hrůša, Ancient Mesopotamian Religion, p. 57. Though Babylon may have not be entirely abandoned or in ruin, as some scholars postulate that our main source for this – a Roman writer – was perhaps exaggerating, see: Dalley, “Occasions and Opportunities”, p. 42.

- Oshima, “The Babylonian God Marduk”, p. 356; Hrůša, Ancient Mesopotamian Religion, p. 58.

- Oshima, “The Babylonian God Marduk”, p. 358, note 51.

- Dalley, “Occasions and Opportunities”, p. 42.

- Stephanie Dalley & A.T. Reyes, “Mesopotamian Contact and Influence in the Greek World: Persia, Alexander, and Rome”, in: Stephanie Dalley (ed.), The Legacy of Mesopotamia (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1998), p. 116. Made you think of the Roman Empire again, didn’t I?

- Tzvi Abusch, “Marduk”, in: Karel van der Toorn et al (eds.), Dictionary of Deities and Demons in the Bible (Leiden: Brill, 1999), p. 548-549; Stephanie Dalley, “The Influence of Mesopotamia upon Israel and the Bible”, in: Stephanie Dalley (ed.), The Legacy of Mesopotamia (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1998), p. 64.

- Michael Seymour, “Ancient Mesopotamia and Modern Iraq in the British Press, 1980–2003”, Current Anthropology 2004, 45 (3), p. 358.

- Daniele F. Rosa, “Ye Go to Thy Abzu: How Norwegian Black Metal Used Mesopotamian References, Where It Took Them From, and How It Usually Got Them Wrong”, in: Lorenzo Verderame & Agnès Garcia-Ventura (eds.), Receptions of the Ancient Near East in Popular Culture and Beyond (Atlanta: Lockwood Press, 2020), p. 107, 109.